“Mama’s form and my own disappeared. In the remaining emptiness, the space where we had been, only affection remained, my love for her and hers for me, this immense and shining we.”

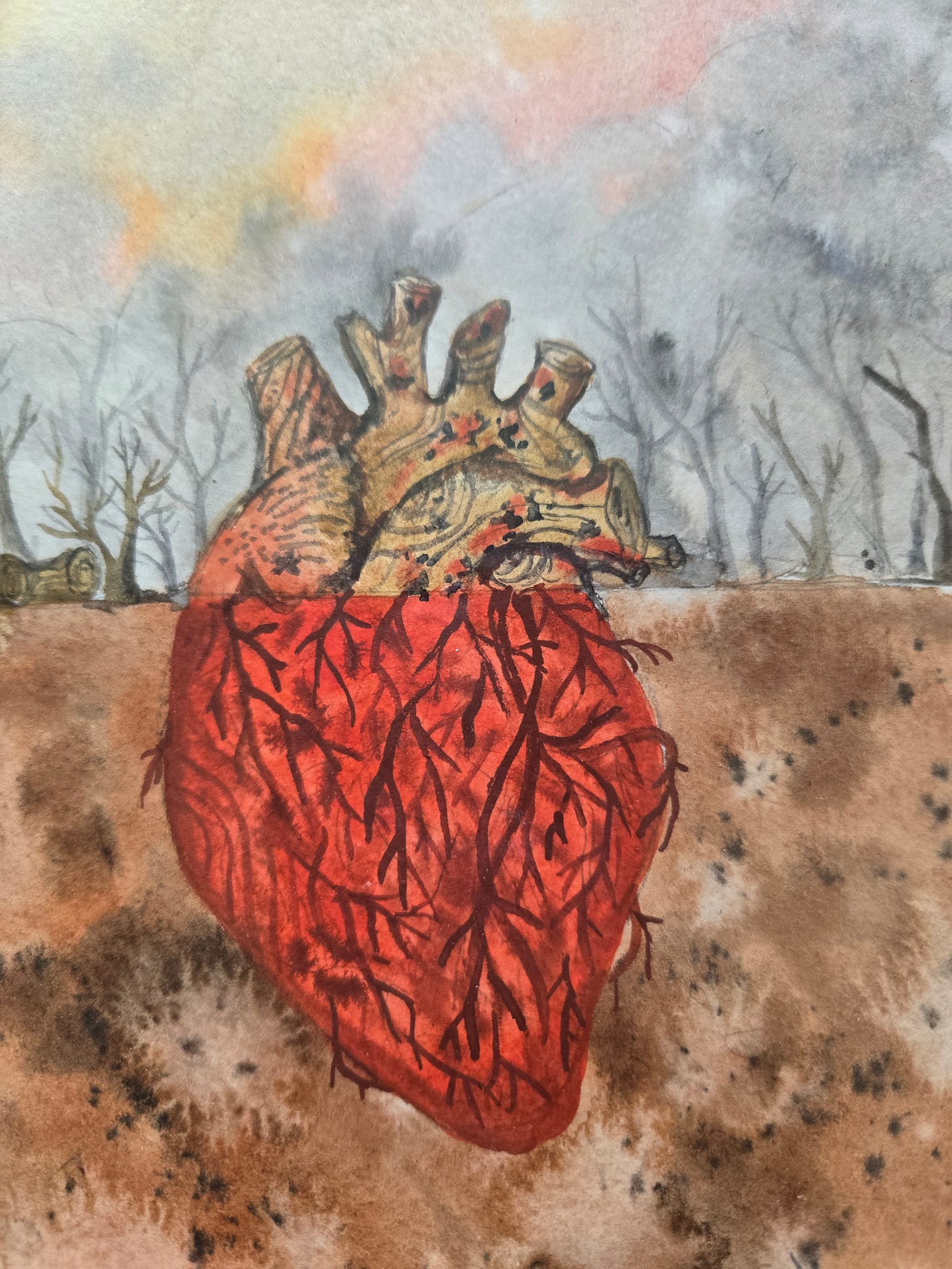

This Animal Body

Several weeks ago, I was on our back deck admiring the new seeds on the maple tree that glowed golden-red in the sun; the cheery yellow-and-scarlet flowers exploding off the crossvine; and about a hundred other indescribably beautiful signs of spring.

Everyone’s blooming, I thought.

Then a new thought popped in my head. We’re blooming.

I’m not sure what prompted it, but it felt good. Like, really good.

Suddenly I wasn’t an outside observer—I was part of something huge and gorgeous. I, too, was golden and glowing, exploding with bright color. The vibrant energy of spring filled every cell and burst forth from my own breast.

It felt so good, I tried we-ing again and again:

By the stream—We are rushing over rocks and gurgling our way to the ocean. With the cardinal—We are singing our hearts out to announce we belong in this place. In the rain—We are free-falling, nourishing all the living things we touch.

Every time I was flooded with happiness and felt a deeper connection to the beings around me. It was such a simple thing that allowed me to experience the joy of the season in a new way.

A We(e) Too Far?

It seemed out of balance to only we with the good things, so when I read the news, I tried it again:

We are being threatened, fired, dismantled, denied due process, detained, deported, displaced, and destroyed.

It was harder to open myself to the despair, terror, rage, and shame that came with these thoughts, but it still felt good in the way that acknowledging an emotion frees me from the exhausting effort of suppressing it, or how feeling something fully connects me to myself and others more deeply.

I had a flash of pride that I was enlightened enough to approach rather than avoid the suffering of others. But it lasted only a second before I realized I’m not enlightened after all, because I still wasn’t willing to we with one other group:

Those causing the current wave of pain.

To be clear, I’m not talking about Republicans, people advocating particular policies, or any one group. My father and husband have taught me that it’s quite possible for someone to genuinely want what’s best for the world and still disagree with me on the specifics of how important things should be handled.

What I’m talking about is doing harm. I’m talking about taking action without caring deeply about the suffering it causes. I’m talking about acting out of something other than love.

It’s happening all over the place. Yes, the Trump administration is taking it to what I find a frightening level, but they’re far from the only ones, and a lack of caring is so ingrained in our culture, it’s never limited to one party or group.

In fact, we all create a lot of harm, if only because we participate in a society that meets its needs through over-extraction, exploitation, and wanton destruction of the natural world. But for most of us—me included—it goes beyond that as well.

All of which makes some questions I’ve been wrestling with even more urgent—

Given the scope of the suffering, how do I act out of love?

Does love mean not condemning the people who perpetuate so much pain? Or is a refusal to condemn them naïve, a misguided attempt to avoid conflict, or—worse—enabling, allowing the attacks to continue?

Even if I wanted to, how could I possibly feel an authentic sense of love for the people who are destroying what I care about most?

And how do I reconcile my own part in this destruction?

To get answers, I had to consult the people who were we-ing long before I came to the table.

Mwe Need to Rewire Our Brains

Dan Siegel, the Harvard-educated psychiatrist and author, coined the term mwe and wrote a book about it to remind us that we are more than a solo, isolated self in a separate body. As he puts it, “we are all differentiated as a me, but we are all [also] linked as a we.”

Ironically, given the number of global threats we’re facing, our survival as a species requires moving our identity from me to mwe and remembering that we’re part of a larger, connected whole. It’s ironic because when we’re under threat, we’re conditioned to do the opposite.

“What the brain does with a threat is it closes down to try to achieve more certainty, saying who’s in the in-group versus who’s in the out-group…[and] if you’re in the out-group, [it says,] I’m going to get rid of you in any way I need to.”

Dan Siegel in an interview with Sounds True

Recent events have made it more apparent how desperately we need to recognize our common connection, but our supersized, state-of-the-art, superlative human brains are getting in the way.

This helped me understand that when people turn the world into us vs. them and cease caring about them, they’re just doing what they’re wired to do because they feel threatened. I believe that’s true, and I’ve certainly fallen into this trap myself, but while it helps me better understand the recent actions of certain heads of state, I still didn’t feel a sense of love toward any of them.

So I turned to beloved Buddhist teacher Thich Naht Hanh and his teaching of Interbeing.

We Are (Literally) the World

In a now-famous talk, Thich Naht Hanh gave a powerful example of what it means to be part of a larger whole. He held up a piece of paper and said that there is no piece of paper as such—only something composed of a tree, a forest, the rain and sunshine, and everything else that allowed the tree to grow.

In other words, each piece of paper contains the entire cosmos. (As do we.)

Once we understand that, we can transform our suffering. He explains this in a way very familiar to me, so I’ll so I’ll share my understanding of it based on my experience:

Pain causes us to pay closer attention to something, whether it’s anger, depression, or your hand on a hot stove. With greater attention comes understanding—of what caused our pain and, if we dig deep enough, of how intimately interconnected we are. This type of true understanding naturally leads to compassion, and together understanding and compassion are the foundation of happiness.

Suffering, then, makes joy possible.. They’re two sides of the same piece of paper—one cannot exist without the other.

Recognizing this relationship between joy and pain requires us to understand the harm people cause each other in new ways.

“You see that the other person has some suffering in him, and you see that he does not know how to transform the suffering… And since he does not know how to handle suffering, he continues to suffer, and he continues to make the people around him suffer. His suffering is spilling over. He is the first victim of his suffering, and you are only the second victim.”

Thich Naht Hanh

This idea—that the pain inflicted by others is secondary to the pain they themselves feel—hit me hard, especially coming from someone who witnessed so much horror and death as a monk during the war in Vietnam.

Something similar inspired a scene in my novel where the main character, Frankie, is talking with her group of animal mentors and discussing the cruelty of humans toward more-than-human beings. Frankie is ready to condemn all people as selfish, violent creatures beyond hope or help. Here’s how the rooster responds:

“You yourself pointed out that you have mirror neurons. On some level, humans must feel the suffering they cause others. How much pain must somebody be in to inflict that much suffering on someone else and not even notice the effect on themselves?”

Roo, This Animal Body

There’s so much suffering spilling over right now.

The We(ight) of the Past

When I was learning how to transform the suffering of my depression, I ran into a principle of pain that shocked me.

I was working with a therapist at the time who focused on getting me to attune to my feelings. First, I took careful notes on a daily chart, noticing and naming each emotion that passed through. Then I learned to how to feel each emotion in my body without trying to talk myself out of it or distract it away.

What I discovered stunned me.

“Sitting with my emotions felt like chewing rocks, an uncomfortable process in which I attempted to break my disappointments and frustrations down into harmless dirt so they didn’t accumulate like sharp scree in my soft organs. My therapist helped me digest not only the pebbles of my day-to-day experiences but also the boulders of my past. As the process wore on longer than I thought it should, I found myself working on giant piles of slag that seemed to appear from nowhere. Where had all this pain come from? I began to wonder if there wasn’t something wrong with me. How could one person with a privileged childhood and no big trauma in their past possibly have so much to work through?

The Dark Light of Depression

“And then it hit me: I wasn’t just working through my own past — this was the accumulated rubble of generations of suffering.”

Feeling the pain of my ancestors in my own body helped me realize the truth of what many are now saying—that if we’re intraconnected, then suffering spills over not just on an individual level, but a collective one. If unable to be healed, pain spills over from groups of people who have gone through large-scale traumatic events like war, displacement, and genocide, and through time from one generation to the next.

Knowing that people harm others because they’ve been severely hurt themselves or have inherited trauma from ancestors wakes some compassion in me. And I truly agree with Roo. But it’s one thing to believe a universal principle about humans in general and completely another to feel the truth of it when reading about horrible things being done to innocent people in the real world right now.

It turns out there was one teaching missing before I could answer my question about how to respond to cruelty with love.

We Are Beside Ourselves with Pain

Content warning: This section discusses suicide in a general, metaphoric sense.

Unfortunately, I can’t recall the teacher who shared this last bit of wisdom. I read an essay on someone’s recommendation, but I didn’t save the source, and now I can’t find it anywhere. All I remember is it was written by a woman. If this is familiar to you and you recognize the source, please let me know so I can credit her and help others find her work.

As I recall the essay, it began with a discussion of the many ways in which humanity’s impact has become anti-life. Not only do we kill an ungodly number of humans, animals, and other beings every day without a second thought, but we’re systematically destroying the land, air, water, ecosystems, and other structures that make life possible.

We know this, too, and have for a while. Yet, as a whole, we’ve been unwilling to do anything more than make minor adjustments to our current way of life.

This insistence on sticking with the status quo is especially odd because we’re not just hurting others. If we’re all connected and make up a larger whole, then it’s inescapable—when we harm others, we harm ourselves. Not to mention the fact that directly and indirectly, we too depend on the things we’re destroying.

This, according to the essay I read, is the crux of the matter.

Humankind is hacking away at our chances of survival so efficiently and exhaustively that it’s almost like we’re doing it on purpose. As if, as a species, we’re struggling with suicidal impulses.

Is it possible that we’re suffering so much—from the threats and crises we’re currently facing; from ancestral, collective, and individual trauma; from being so disconnected from ourselves and the wider, living world—that on some level, deep in our subconscious, we’ve lost all hope? Stopped valuing our own life and well-being? Assumed that death is the only way out of our pain?

Ironically, this possibility gives me a lot of hope. Just as many people with suicidal thoughts or impulses have found their way to a more hopeful future, so too can humankind. It’s not an implicit part of who we are that makes us harm ourselves and others, but a cyclic response to all the pain that we’re carrying.

And as Thich Naht Hanh pointed out, suffering, once transformed, leads to joy.

It also gets me closer to an answer to my earlier questions.

When I think about people’s worst actions as subconscious yet intentional self-harm, I can’t help but feel profound compassion for the immensity of the anguish that makes them want to hurt themselves. They unquestionably deserve love and mercy.

Correction: We unquestionably deserve love and mercy.

And, just as much, if someone I knew were trying to hurt themselves, I would do everything possible to stop that harm from happening. Right now, that means finding ways to put my weird, awkward, and messy magic to work helping those who are suffering and, in whatever ways are available to me, trying to prevent further suffering.

I’m finally beginning to realize for myself the truth that wise people like Martin Luther King, Jr. figured out a long time ago—that love and compassion don’t ever get in the way of protecting the vulnerable or ending attacks.

In fact—just like me and the maple tree, just like joy and suffering, just like the people destroying the world and me—stopping harm and acting from love are really one and the same thing.

If you are suffering with suicidal thoughts, call or text 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline or go to the International Association for Suicide Prevention website to find helplines and other resources worldwide.

If you’ve recently been laid off or are in danger of being laid off soon and you’re not sure what to do next, I’d like to offer access to an online class I developed several years back—Passion Quest: 5 Steps to Find Your Calling in a Fear-Based World—for free. Its videos and PDFs of action steps walk you through the process I use to help my one-on-one coaching clients find a fulfilling and meaningful path that addresses their deepest desires and their need for an income. And if you want more ways to work through each step, I’m happy to send over additional exercises and practices I’ve developed since I made the course.

Though I originally intended to offer this to federal employees, my husband made the good point that they aren’t the only ones in need, so I’m happy to extend this offer to private sector employees as well.

To get free access to the course, just send me an email at me@meredithwalters.com.